We currently do not have effective vaccines or antiviral drugs for most of the viral diseases that afflict humans. Antiviral therapies that enable long-term control over human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and cure chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) have been landmark successes in the treatment of viral infections. These therapies work using multiple direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) that halt viral replication by potently inhibiting or deranging the function of viral proteins, generally enzymes such as viral polymerases and proteases. Development of our current arsenal of DAAs has required significant investments that cannot be easily duplicated to combat the hundreds of other existing and emerging viral pathogens on an individual basis. Prioritization of viral pathogens for drug development efforts is challenging and unpredictable, currently requiring a balance of efforts to develop therapies for widespread viral diseases that affect hundreds of millions annually, such as chronic hepatitis B and human influenza viruses, with efforts to develop countermeasures against less predictable emerging and re-emerging viruses, such as Zika virus and SARS CoV-2, for which delaying until the virus is a major threat makes it difficult to have an impact on the immediate crisis.

Compounding these challenges is the emergence of drug resistance, which, as shown for HIV and HCV, can occur rapidly during monotherapy with only a single DAA. Many of the most threatening viruses (e.g., influenza, dengue, Chikungunya, Zika, respiratory syncytial viruses) have RNA genomes that mutate rapidly due to limited or no proofreading function in the viral polymerase. For viruses like these that cause annual epidemics and are transmitted constantly, resistance to a single drug that inhibits a viral enzyme is expected to rise rapidly and may already exist in nature, as was observed for the influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir and endonuclease inhibitor xoflusa. Another inherent limitation of monotherapy against a single target is the high systemic exposure required to ensure sufficient inhibitory potency in vivo and the emergence of drug resistance. While combination therapy with multiple DAAs that act via independent targets and mechanisms is a proven way to achieve the necessary level of antiviral potency and avoid resistance, our development of these combinations is resource limited. Due to these challenges, antiviral strategies that use alternative targets, mechanisms, and modalities to combat viral diseases are of considerable interest in developing new classes of antivirals with increased spectrum of activity and higher barrier to resistance.

Targeted protein degradation (TPD) has emerged as a pharmacological strategy in which a small molecule is used to target a protein of interest to a cellular degradation pathway. This has most commonly been accomplished by using bifunctional chimeric molecules to recruit a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase to the target protein of interest, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. While TPD-based drugs have advanced rapidly with >20 currently in clinical for cancer and inflammation, application of TPD in the area of infectious diseases has only recently begun to emerge.

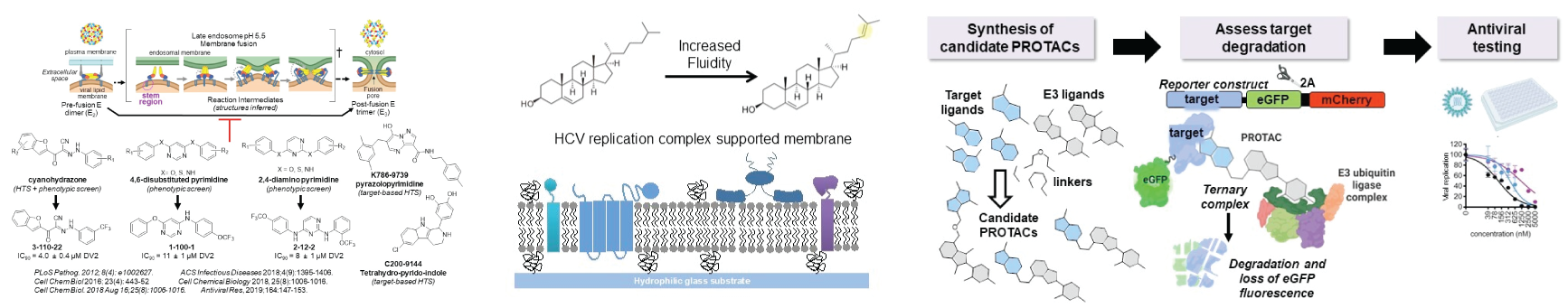

Our lab has been at the forefront of developing targeted protein degradation (TPD) as an antiviral strategy. Our approach has been to synthesize bifunctional molecules (known as “degronimids,” “PROTACs,” or “degraders”) that have a ligand for the target of interest covalently linked to a ligand for a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase. Rather than inhibiting or deranging the function of the viral target protein, the degrader molecule induces formation of a ternary complex with an E3 ligase, leading to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the target protein. Unlike small molecule inhibitors, which have occupancy-driven pharmacology and thus must bind with high affinity to exert significant antiviral activity, degraders exhibit event-driven pharmacology and only require affinity and residence time sufficient to allow formation of the ternary complex. Due to this tolerance of lower affinity binding, we have hypothesized that antiviral degraders may be better able than classical inhibitors to inhibit genetically diverse viral species and to suppress potentially resistant mutants that arise during drug treatment. As proof of concept, we used telaprevir, an FDA-approved inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3-4A protease, to develop degraders of HCV NS3 and to show that NS3 degrader DGY-08-097 inhibits telaprevir-resistant mutants.

We have since extended our efforts to develop TPD-based antivirals against a variety of other viral proteins, with a keen interest in viral proteins that are considered “undruggable” due to their lack of a classical active site.

Development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) is limited by (1) the small number of validated antiviral targets, most of which are viral enzymes (e.g., polymerases, proteases); (2) the relatively low barrier to viral resistance when these DAAs are used as monotherapies; and (3) the narrow spectrum activity of most of these agents (“one bug, one drug”). Viral envelope proteins, like proteases and polymerases, have conserved structures and well-defined biochemical functions within the replication cycle of related viruses. Notably, targeting the viral fusion and particle assembly functions of viral envelope proteins is attractive because the conserved structures critical for these processes generally involve intraprotein contacts that are not surface-exposed and thus are less likely to diversify due to antibody-driven selection. Despite this potential, viral envelope proteins remain poorly exploited as a target class for antivirals development. Structure-based inhibitor design has been difficult due to the proteins’ lack of obvious, conserved sites where small molecule-binding can inhibit envelope protein function. The absence of appropriate target-specific, biochemical assays has limited high-throughput screening (HTS) efforts and medicinal chemistry optimization of lead compounds identified in phenotypic or computational screens. Furthermore, targeting viral envelope proteins as an antiviral strategy has been questioned due the presence of many functionally redundant copies of the protein on each virion. Focusing on dengue virus and its flavivirus relatives as an experimental model, we have identified multiple small molecule inhibitor series that bind to the DENV envelope protein, E, and inhibit E-mediated membrane fusion during viral entry even when a minority of copies of E on the particle are inhibitor-bound. We have shown that these compounds bind in a pocket between domains I and II and inhibit West Nile, Zika, and Japanese encephalitis viruses due to at least partial conservation of this site. Our current efforts are focused on advancing these compounds for proof of antiviral efficacy in in vivo models and on better understanding their mechanism(s) of action and on discovery of small molecules that interfere with the production of new virions by binding to E. This potential dual mode of action is of interest because it may increase antiviral potency and also raise the barrier to resistance caused by suppressor mutations since mutations that rescue one of these functions may not rescue the other function.

Recent successes in cancer drug discovery have exploited the chemical reactivity of specific cysteine thiols, which allows potent and selective covalent inhibition of oncogenic kinases. In some cases, the covalent mechanism of these inhibitors has mitigated the need for extensive optimization of pharmacokinetic properties prior to proof-of-concept in vivo studies because full and irreversible inactivation of the target can be achieved under conditions of transient exposure. Inspired by these successes, we screened a library designed to target the host reactive cysteinome and identified QL47 as a covalent, host-targeted small molecule inhibitor of Flaviviruses and several other viruses of high biomedical significance. We discovered that QL47 inhibits translation with a stronger effect on virus versus host. Remarkably, QL47 and related compounds affect translation driven by the cricket paralysis virus IRES, which can initiate translation in the absence of any host initiation factors. We are currently studying QL47’s target and mechanism of action.

Lipid membranes have essential functions in many biological processes, but in many cases we do not know the specific lipids involved or how these lipids affect membrane function and the biological processes that occur in (or on) the membrane. A handful of studies have demonstrated that changes in lipid composition can significantly affect signal transduction and the efficiency of membrane-associated enzymes. This suggests that membranes are not passive scaffolds but rather can be active regulators of biological processes. Knowing how membrane-localized biological processes are affected by the biochemical and biophysical properties of the membrane is therefore critical to understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes.

We have approached viral RNA replication as a system for studying lipid membrane specificity and function. Many RNA viruses localize genome replication to specialized membranes. At a rudimentary level, this serves the dual purpose of concentrating reactants and catalysts in the same place while also shielding the viral RNA from host defenses. This simplistic model intuitively makes sense but begs the question: can all membranes function equivalently in supporting viral RNA replication? This seems unlikely. To examine and explore these issues, we have utilized the tools of analytical chemistry to discover lipids specifically upregulated during hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in vitro; performed molecular virology experiments to show that this lipid, desmosterol, functionally important for HCV replication (and not just a marker of infection) and to show that viral RNA replication is the viral process affected when desmosterol is depleted from the cell; adapted Raman-based and fluorescence imaging to show that the lipid colocalizes with sites of viral RNA replication; and developed semisynthetic supported lipid bilayer and proteoliposome systems to interrogate how changes in desmosterol content affect membrane fluidity and RNA replication. We have further shown that HCV causes the increase in desmosterol through cleavage of DHCR24, the enzyme that converts desmosterol to cholesterol, by the viral NS3-4A protease. We are currently building on this work to develop experimental platforms that enable us to interrogate how lipid composition of the membrane affects HCV RNA replication and replicase complex formation and function. We are also interested in extending these types of analyses to other viral systems.